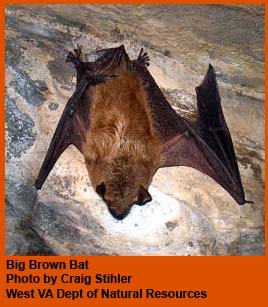

Basic Bat Info

(Information from Bat Conservation International, www.batcon.org )

Bats are essential to the health of our natural world. They help control insect pests and are vital pollinators and seed-dispersers for countless plants. Yet these wonderfully diverse and beneficial creatures are among the least studied and most misunderstood of animals.

Centuries of myths and misinformation still generate needless fears and threaten bats and their habitats around the world. Bat populations are declining almost everywhere, especial due to the devastating White-nose syndrome. Losing bats would have devastating consequences for natural ecosystems and human economies. Knowledge is the key.

The more than 1,200 species of bats – about one-fifth of all mammal species – are incredibly diverse. They range from the world's smallest mammal, the tiny bumblebee bat that weighs less than a penny to giant flying foxes with six-foot wingspans. Except for the most extreme desert and polar regions, bats have lived in almost every habitat on Earth since the age of the dinosaurs.

Bats are primary predators of night-flying insects, including many of the most damaging agricultural pests and others that bedevil human populations. Diverse bat populations help control agricultural pests in farmlands and orchards, vastly reducing the need for chemical pesticides. More than two-thirds of bat species hunt insects, and they have healthy appetites. A single little brown bat can eat up to 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in a single hour, while a pregnant or lactating female bat typically eats the equivalent of her entire body weight in insects each night.

Almost a third of the world's bats feed on the fruit or nectar of plants. In return for their meals, these bats are vital pollinators of countless plants (many of great economic value) and essential seed dispersers with a major role in regenerating rainforests. About 1 percent of bats eat fish, mice, frogs or other small vertebrates. Only three species, all in Latin America, are vampires. They really do feed on blood, although they lap it like kittens rather than sucking it up as horror movies suggest. Even the vampires are useful: an enzyme in their saliva is among the most potent blood-clot dissolvers known and is used to treat human stroke victims. Even bat droppings (called guano) are valuable as a rich natural fertilizer. Guano was a major natural resource in the United States a century ago, and it's still mined commercially in many countries.

Some biologists consider bats a "keystone" component of ecosystems in parts of the tropics and deserts. Without bats' pollination and seed-dispersing services, local ecosystems could gradually collapse as plants fail to provide food and cover for wildlife species near the base of the food chain. Consider the great baobab tree of the East African savannah. It is so critical to the survival of so many wild species that it is often called the "African Tree of Life." Yet it depends almost exclusively on bats for pollination. Without bats, the Tree of Life could die out, threatening one of our planet's richest ecosystems.

All but four of the 47 bat species found in the United States and Canada feed solely on insects, including many destructive agricultural pests. The remaining species feed on nectar, pollen and the fruit of cacti and agaves and play an important role in pollination and seed dispersal in southwestern deserts.

The 20 million Mexican free-tailed bats at Bracken Cave, Texas, eat approximately 200 tons of insects nightly. A colony of 150 big brown bats, which often roost in tree cavities, can eat enough cucumber beetles each summer to eliminate up to 33 million of their rootworm larvae, a major agricultural pest. More than half of American bat species are in decline or already listed as endangered. Losses are occurring at alarming rates worldwide.

For more information about bats and bat species, go to:

- Bat Conservation International - http://www.batcon.org

- USDA Forest Service - http://www.fs.fed.us/biology/wildlife/bats.html and http://www.fs.fed.us/global/wings/bats/welcome.htm

- Lubee Bat Conservancy - http://lubee.org/

- National Wildlife Federation - http://www.nwf.org/Wildlife/Wildlife-Library/Mammals/Bats.aspx

- Multi-agency web site about White-nose syndrome - https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/

White-Nose Syndrome

White-nose syndrome is a disease that is killing hibernating bats in eastern North America. WNS was first documented at four sites in eastern New York 2007. After that, photographs taken in February 2006 were found, showing affected bats at another site.

Named for the white fungus on the muzzles and wings of affected bats, WNS has rapidly spread to many sites throughout the eastern United States and into Canada. The fungus that causes WNS has been detected as far south as Mississippi. Researchers associate WNS with the newly identified fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which thrives in cold and humid conditions characteristic of caves and mines used by bats.

Bats affected with WNS do not always have obvious fungal growth, but they may behave strangely within and outside of their hibernacula (caves and mines where bats hibernate during the winter).

(From the White-nose syndrome.org web site. For more information about WNS, go to https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/.)